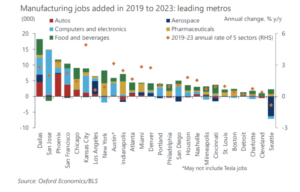

Colorado’s advanced manufacturing ecosystem is deep in aerospace acumen; established if underpublicized in bioscience and food and beverage; up and coming in battery and EV-related applications; and awakening as a semiconductor node, where America’s newfound interest in a national chip industry has raised the stakes for companies and communities.

It would be back to the future for Colorado Springs. As the Colorado Springs Gazette has noted,

“The semiconductor industry has a long history in Colorado Springs, starting when NCR opened the first local chip plant off Fillmore Street with 12 employees in 1975.

The plant Microchip operates was started by Honeywell in 1977, acquired by Atmel in 2009 and Microchip in 2016. At the industry’s peak, nine companies operated semiconductor manufacturing plants in Colorado Springs employing thousands of people and local boosters promoted the city as ‘Silicon Mountain.’”

Lindsay Pack and the team at Colorado Springs standout dpiX – now InnovaFlex Foundry – are intent on reimagining a new semiconductor ecosystem throughout the state. I interviewed Pack before last month’s CHIPS Act-related developments were announced. We’ll connect the dots from that news in a follow up column.

First, my chat with Pack:

Bart Taylor: I like the name, the reference to “foundry.” It’s now a modern, relevant term that connotes your ambition to expand your horizons in the semiconductor industry.

Lindsay Pack: Yeah, we were hoping that it would help make us a little bit more understood!

BT: So, speak to the new vision, reflected in your rebranding, and the future of the company if you would?

LP: When I joined, the focus really was on X-ray manufacturers. And understandably so: that’s our history. And I don’t want to stop supporting that industry. It’s such an important space. I mean, pretty much everyone has come in contact with one of our semiconductors via X-rays, right, at some point in their life. It’s clearly important. It is a very steady business – if not a lot of growth.

It’s also very price competitive. Clearly, fabs in China can produce things much more inexpensively than we can. Recognizing that we’re in a steady-state business with very low margins, I don’t want to abandon that space, but I need to diversify.

And when I think about who we are, I get excited about the future. We’re the only company in the United States that makes the type of semiconductors we do, we do it at scale, and we’re not a big-box firm. It’s not just, “Well, this is the semiconductor I make, take it or leave it.” We can actually work through innovation, we can partner in an IP-protected, secure environment to help develop very custom real solutions for unique problems, things that never were possible before.

The question I’ve asked is, “Why are we not more focused on U.S.-based products?” when there’s such high demand now in space, defense, and other markets. Let’s get focused on that. Let’s continue being great at X-ray detectors. But we’re going to use that foundation now to be great at other things as well, focused on things that really should be here in the United States.

BT: There’s opportunity for sure – though different, perhaps, from “conventional wisdom.” I just read Chip War (by Chris Miller), and he certainly puts your vision in context. One of the misconceptions about the U.S. semiconductor industry is that we don’t make a lot of chips here or support a thriving semiconductor industry. In some ways, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

As Miller points out, the U.S. is still a global leader in chip design and production. In fact, we make much of the equipment used offshore to manufacture the advanced semiconductors that represent the future, and we also design them here. Intel is manufacturing semiconductors in the U.S. that power a generation of servers and PCs. Apple buys radio-frequency chips for their iPhones (and other semiconductors) from U.S. suppliers in California and Texas, for example – and designs the chips that power the iOS operating system.

But they can’t manufacture those chips here: they’re manufactured by TSMC in Taiwan. As you’ve pointed out, upwards of 80 percent of those chips are manufactured outside of the U.S.

How do we square-the-circle? In addition to sharing the cost for TSMC to build new factories in Arizona and elsewhere, to build a new advanced manufacturing capability, are we in a position to also build out the current U.S. semiconductor ecosystem and get back in the game that we’ve allowed to move offshore to Taiwan in particular?

LP: I think largely, yes, and you’re right, a lot of design has been able to stay here in the United States.

But we have been losing those capabilities over time. I’ll tell you that for us, no one in the United States had the knowledge or expertise whatsoever for me to work on the new technologies that I need to work on. I have to recruit internationally to be able to bring in that expertise. Because the U.S. did shift a lot of that manufacturing offshore with the intent of maintaining the design and engineering expertise here.

But it’s so hard to separate manufacturing from design, especially when these processes are the design. And I don’t want us to be under the impression that we can keep design here in the United States and just simply have manufacturing somewhere.

We used to be able to get our equipment, components, all those things here in the United States. But as all of that production started shifting overseas, guess what, the suppliers did, too. So we do have to rely on many Asian suppliers to support the equipment that we have in the fab because there just isn’t anyone here in the United States that can provide those services.

What I think is so important with chips is that it’s not just us expanding, or our neighbors down the street that are producing some other sort of chip. It’s that when we invest in this, we need a center of mass to be here once again – where it makes sense for all of those suppliers to be located here to actually service companies here. I understand why for them, it wasn’t practical any longer to maintain business here. It was the unintended consequences of thinking, “Oh, well, we’re just moving manufacturing.” Over the years, it really eroded much more of the semiconductor ecosystem. As you point out, we have semiconductor expertise and we have semiconductor manufacturing. But I think we are at that pivotal moment where if we don’t do something to reestablish the manufacturing supply chain, we’ll lose the upper hand in the future of semiconductors.

BT: Your language could be straight out of the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act – the legislation intended to usher in a new era of investment in America’s semiconductor ecosystem. One derivative of CHIPs – the $10B Regional Innovation Hub competition – has attracted interest from several groups in Colorado. Are Regional Innovation Hubs the right mechanism, the right platform, at the right time, to supercharge the semiconductor supply chain? [Editor’s note: The Biden administration has announced finalists in the RIH program – view the list of designees here.]

LP: I think there certainly is a foundation here that we can build from to help companies that may not have been directly playing in this space to now have the opportunity to diversify. They may have fundamental capabilities, and they can diversify in this space as well.

This R&D component of CHIPs is so important – equally as important as funding the expansion of manufacturing. Because we don’t want to bring manufacturing back here just to lose it again tomorrow; we need to bring it all back. We need to be able to continue to innovate so that, tomorrow, we’re competitive and have the technology we need for our country. It’s why the R&D part is so important.

Even things like materials: we need alternatives to ones that, you know, might be challenging to get because of the Ukraine war, for example. I know we certainly deal with some materials – gases in particular – that you can’t get anywhere else. And so how are we thinking about alternatives? Again, it’s going to require research and development, because you can’t just swap out one gas for another gas and think everything’s going to work exactly the same. So, I think that’s a key part of the CHIPs act.

And a key part when we think about the supplier aspect is it’s not just ‘lift and shift – like for like.” There will be development that’s going to have to be involved in that process. And then, you know, the experience that I’ve had, as we’ve talked to some of these companies here in the United States, they’re like, “Yeah, well, we really haven’t put a lot of effort in investing into some of these technologies and capabilities, even if we used to do some of those things, because there hasn’t been a market.” And we’ve approached them and said, “Hey, with CHIPs act, hopefully we’ll get funding. And if we get funding, then we want to invest in this. What would that mean for you? Could you be our service provider? Could you actually continue to invest if we’re purchasing from you?”

That’s the idea. It’s a cascade and a trickle effect as we start to bring these things back. The investment then goes, you know, into the other pieces and the whole supply chain then benefits and is able to stand up because it will finally make sense.

It’s going to take the collaboration; that’s why the hub model is really valid. It’s going to take the collaboration of more than one company. Sure, an individual company can do research – it supports their own development and production. But for us to really move the needle and stay ahead of the technology, it’s going to take a collaborative innovation approach.

BT: By way of collaboration, do you envision a robust semiconductor ecosystem developing in Colorado?

LP: I do see the ecosystem developing in Colorado. I love Colorado as a whole, but for one, I think Colorado Springs also has such a unique culture that it’s very collaborative. My background isn’t DoD (Department of Defense), and I haven’t tried to sell into that space and really understand how to do business there. But guess what? Colorado Springs is really good at that. It’s easy for me to raise my hand and say, “Hey, you do business over there, you know how this works. I need help!” And people have been so gracious to just come alongside to make the connections and the introductions and help you find the paths through this process. That is one of the things I do love about Colorado Springs in particular.

And I’m hoping that we continue to expand that outside of just Colorado Springs and do that more effectively across Colorado as a whole. But you know, you’ve got Microchip here, you’ve got Entegris moving into Colorado Springs right now as well. And I think the really cool thing is all three of us are part of the semiconductor ecosystem, but we are not competing with each other. Together, we can utilize a lot of the same suppliers and, ultimately, further that same mission with the semiconductor industry in the United States.

And I think you start to see this again: that center of mass that I talked about. Now it becomes more interesting for those additional suppliers to continue to move into this space. In Colorado Springs, we used to be great at semiconductors. We have that foundation, those fundamentals. And it’s very exciting for me to see all the investment that’s here back in Colorado, again, focused in this space. But now with the long game in mind.

Bart Taylor is a Moss Adams BDE in Manufacturing & Consumer Products, Food/Beverage & Agribusiness, and is founder and former publisher of CompanyWeek manufacturing media. Reach him at bart.taylor@mossadams.com

Next time: A look at how the Regional Innovation Hubs competition played out for Colorado.